The films of the internationally renowned artist Dimitris Papaioannou, Nowhere (Director’s Cut), and Primal Matter, the entire work in seventeen minutes, were screened on Wednesday, March 13th, at Stavros Tornes theater, within the framework of the spotlight hosted by the 26th TIDF, on the great Greek artist. After the screening, a discussion with the Festival’s Artistic Director, Orestis Andreadakis took place, followed by a Q&A with the audience. Dimitris Papaioannou signs this event’s design and showcases the video installation, Inside, along with the backstage video, Backside, at MOMus - Experimental Center for the Arts. Eva Stefani’s documentary Bull’s Heart, produced by Onassis Culture, was also screened at the Festival as a work-in-progress. It follows Dimitris Papaioannou’s play, Transverse Orientation, that was produced by Onassis Stegi during its showcase in European stages.

The film Nowhere, conceptualized, filmed and edited by Dimitris Papapioannou, is a film version of the theatrical production of the same name, commissioned and produced by the National Theatre of Greece to inaugurate its renovated Main Stage in 2009. The film was unveiled for the first time in the context of the 26th TiDF’s spotlight on Dimitris Papaioannou. Primal Matter is a condensed cinematic summary of Dimitris Papaioannou’s original production, Primal Matter, presented in 2013 at the Athens Epidaurus Festival. Originally spanning one hour and fifteen minutes, this live performance featured Dimitris Papaioannou and Michalis Theophanous. It was filmed by Stefanos Sitaras, while its 15-minute version was edited by Dimitris Papaioannou.

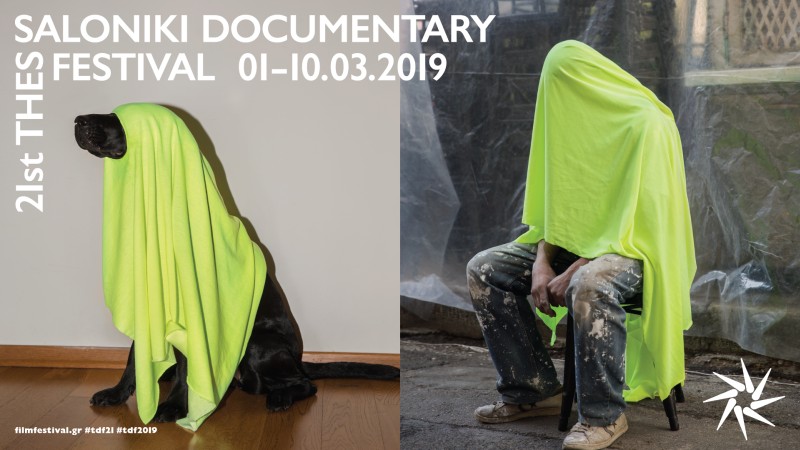

Before the screening, the Festival’s Artistic Director, Orestis Andreadakis took the floor, saying: “Good evening, we welcome you to another screening that focuses on this amazing and important artist. A tribute that began with the poster of the Festival, unveiling today another aspect of his multifaceted talent, aside from painting, directing, choreographing, and filmmaking. Without further ado, we welcome Dimitris Papaioannou.”

Taking the floor, Dimitris Papaioannou said: “Here, in Thessaloniki, there are three attempts to document a live event in a specific way, so that someone can relive it in a different manner. Inside, is a still, six-hour long monoplane. Now, you are about to watch Nowhere, a 35-minute performance I filmed with an amateur camera, from many different angles, during the various performances. Ultimately, I chose to intertwine only long shots, completely abolishing the frontal approach of the viewer, and attempting a cubist approach to the space. Then, we will see a third sample, Primal Matter, my favorite work. It was filmed by Stefanos Sitaras, with Nikos Nikolopoulos’ participation, while the editing was done by me. It is a 17-minute-long summary of the production, which functions as its condensed cinematic version. There is also a fourth sample, accompanying Inside; Backside, where there is no need to capture a live event, as is the case of the other three samples. Backside is filmed with a single hand-held camera, during the six-hour feat carried out by the performers in Inside. That is where one can witness my preferences in cinematic language.”

Following the screening, a discussion with the audience took place. In response to Orestis Andreadakis’ question about how the human figure is related to the background, how it was reflected on stage, and how much he was influenced by his teacher, Yannis Tsarouchis, Dimitris Papaioannou answered: “In the National Theatre of Greece, which was just setting out for a new era, I imagined a play about theater, itself. As I don’t use speech, what I imagined to be useful was the mechanisms of the theater itself, as a system of mirroring society on stage. One of the best ways to attempt approaching this subject was what we call anthropometry. Anthropometry is expressed beautifully in Japanese square meters, referred to as tatami, a small rectangle in which a human figure fits. How many tatamis are there in a room? We tried to count the space by the stride of a human, the lying human body, the relationship between accumulation and isolation, the fall. Theater has a black background, and when you decide not to use sets like in the National Theatre of Greece, the mechanisms of the theater are utilized as a set. Things turn dark, quite literally, because theaters are black. Therefore, many issues arise. During filming, I found out that the lights reflected on the floor in such a way that, from other angles, the shadows and figures were caught on camera, creating a feeling which was more interesting to me. That is, the anonymous crowd, the units within the space. This element is also related to the paintings of Zaphos Xagoraris, who was my artistic collaborator in Nowhere.”

Regarding the motivation that made him leave painting and shift to theater, Dimitris Papaioannou stated: "For me, the motivation became very clear when I was around 18 and had left home, living in Athens and selling my paintings. In a class and at an age to which I did not belong, I had no way to have contact with my fellow human beings. Comic books were the first step to gain direct contact with my generation; to do an art that by its very nature is cheap and to be able to share some stories, in addition to searching for the ideal form. I was lucky to have lived through the era of these magazines, because when my stories were first published, I began to feel like I was gaining connection. Until I discovered theater, which is something completely different and direct." Regarding his relationship to movement, he noted that he "comes from a repressed childhood-teenage athletic background. When I was nineteen, I met Mary Tsouti, my dance teacher, and all this inhibited physicality found a passage and it was released. I never became a dancer, but I channeled the biological drive and the urge to express myself through movement into my work. However, my job is not to incite movement; it is to create these works as dramaturgy. I am simply the choreographer of my work.”

In response to another question, Dimitris Papaioannou touched upon the way he constructs a performance: “The creative process is a chaotic improvisation of a group of people on a few ideas. The director's responsibility is to make people feel more comfortable. So, we're a group of crazy people, working on what, for example, a piece of paper sounds like. We film all of that and slowly collect anything that's somewhat interesting. After two months of such a chaotic game, the deadline is approaching, and I have to decide, as a director, that I have to craft something out of these pieces I have collected. Thus, begins for me the most unpleasant process, which is to try to synthesize them, as well as the most unpleasant process of all; deciding this game of composition has reached its conclusion. The truly difficult thing to admit is that, unfortunately, it's still no better than what I can do.”

Orestis Andreadakis pointed out that Dimitris Papaioannou’s works are overtly open, asking if it's something he's pursuing. “The work is very specific. What it means and what it does to each person is something I don't want to control. In fact, I think I'm a little more symbolic than I'd like in my works. I would like to be even more multi-dimensional. I like what I do to be very specific, in order to be open. To be obsessively clear, so that it can reflect each person in it. I don't want it to mean anything, nor to teach anything. I do not want to express targeted opinions, I want what I do to be completely polished, so that it can function as a mirror.”

Regarding Pina Bausch, and how he felt about his work, he replied: “Twice in my life I have had to respond positively to something because I would regret it on my deathbed. The first is the opening ceremony of the Olympics and the other is Pina Bausch. These are death sentences. You are speaking to me about Pina Bausch, while I’ve done seventeen other works. And all the Greeks tell me “Your works are so beautiful, the Olympics were unforgettable,” which is as much a blessing, as it is a curse. There are some things that, when fate thrusts them before you, you can't help but take the risk. The work with the Pina Bausch team was difficult, particularly soul-crushing, but in the end it turned into an affectionate experience of immense proportions for us and the team we worked with. We are all grateful that we did it. It is a work that was never finished, but it was presented many times. Non Finito!” Immediately afterwards, he referred to the opening ceremony of the Olympics: “You ask me assuming that it paved the way for the international career that I now enjoy. I ask you: Name one artist, who was in charge of an Olympics opening ceremony. The global contemporary art system snubs anyone who engages with such commercial themes. I didn't start this process to make a career out of it. They're not communicating vessels. Twenty years ago, when this happened, and twenty-three years ago, when it was suggested to me, the world of the entertainment industry had nothing to do with the system I was working in. That world always needs artists to do the work, which is nothing more than state propaganda. Every state sells its culture, as if making a commercial spot about its status to the world. Perfectly fair, but that's all it is. This is a job that only an artist can do, but it's not art."

On the cinematic dimension of his work, Dimitris Papaioannou remarked: "I have become an enthusiastic editor, I try to create testimonies of my work, which are not as boring as a mere recording of the performance." As for his relationship with Yorgos Lanthimos, he stressed the following: "I appreciate Yorgos immensely, I am proud to be his friend. When we were much younger, we met through Konstantinos Rigos. In four of my own performances, he took up the cinematography (Medea, Dracula, Human Thirst and Storm)."

On how his voice has helped the LGBTQI+ community gain greater visibility, Mr. Papaioannou stated: "I never had any intention of dedicating my life to becoming an activist. I ran away from home at eighteen years old because I wanted to be an artist, which is my nature, and because I wanted to be an openly gay man, which is also my nature. It was purely a matter of personal dignity. I also have a difficulty with being constrained. Once I ran away from home and became financially independent, I promised myself that I didn't want to be in any environment where I had to lie about who I was. And things were easier than I thought they would be. Except for some bullying in some cases, I didn’t encounter any other issue. In retrospect, there are people of all ages who come up to me -and I am deeply touched- and tell me that my work and my personality helped them to accept themselves and imagine that such a life can be experienced without guilt. My popularity reached its peak after the opening ceremony of the Olympics, when I became a kind of a national hero. I decided to channel the force of this otherwise useless popularity into something I considered useful: I gave the first interview to 10%, a magazine of the gay community. I thought that if a child in the countryside is looking for something to give him joy, he will feel something beautiful if the man who is now considered a national star reminds him that he is an openly gay man. I never wanted my art to be perceived as queer art. Especially now that it’s a trend. I have always been proudly and openly gay, but I never wanted to blend the natural homoeroticism of my works with the false belief that I am only serving a single portion of society, while I yearn to work for all my fellow human beings. We are in Thessaloniki, the city of the great poet, Dinos Christianopoulos, who once said: ‘I am an erotic poet, working on my share in the field of love. If I am a good poet, then poetry will cultivate it.’ This says it all. At my age, I have been moved numerous times by generations of children coming up to me and thanking me for this. It was never my intention. I wanted to live a life with dignity. I've dedicated my life to creation, yet there's this parallel field of love as well, and I feel grateful that life has brought it on and I've provided relief."